News

All Articles

Company

Industry

Products

Conservation

Fishing

Grady-White Fanatics

All Years

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2015

October might just be one of my favorite months. It marks the return of daytime blitzes along the beaches, the opening of hunting season, and the final harvest from the garden. As the leaves begin to fall and temperatures plummet, I will begin craving the return of cold-weather comfort foods to my kitchen. It’s time to make chili, pot roast, beef stew, and chowder. It’s time for Sunday feasts, served with a cold beer, a warm fire, and a side of football.

October is also prime time for one of my favorite fall-run fishes, the lowly tautog. While most anglers will be chasing the last stripers or tuna of the season, I will be more inclined to spend my free time soaking crabs for tautog. I’ll have chowder on my brain and will be looking to pack away some prime chowder meat to get me through the long winter ahead.

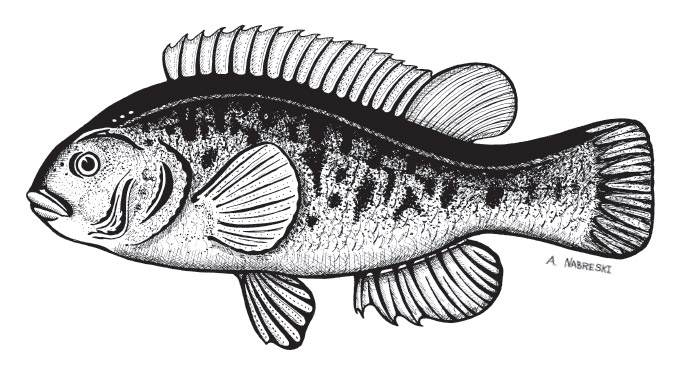

There is nothing glamorous about these buck-toothed fish. They’re short and stubby. They have oversized, rubbery lips. They are slimy, and they have little tails that look too small for their robust bodies. But what they lack in aesthetics, they make up for with their bulldog antics when hooked. The same muscles that provide their brute strength also yield beautiful, firm white fillets.

Tautog are powerful fish that will use every ounce of their strength to avoid capture. Big ‘tog put up an amazing fight, and many gain their freedom by causing cut-offs among the rock piles they inhabit.

When looking for tautog, you want to find the gnarliest bottom structure available. Wrecks, wharf pilings, piers, jetties, and boulder-strewn bottoms are all likely places to start your quest. These fish like to hang tight to structure, so it’s imperative that you anchor up directly above your target zone. Anchoring is usually the best way to go, as drifting will lead to abundant hang-ups on the bottom. Using a chum pot with crushed up crabs, mussels or clam shells will always improve your odds. Shorebound anglers can also get in on the action: look for docks, jetties or piers with deep water nearby.

Tautog Jigging

The past few seasons I’ve been experimenting with using baited jigs for tautog, and so far I’ve been impressed with the results. Several local companies have recently begun selling jigs designed specifically for tautog. I’ve tried jigs made by TidalTails and Run Off Tackle, both of which worked well. The main benefit is improved sensitivity, as your line is essentially tied directly to the hook. Simply thread on half a green crab, and let it sit on the bottom, with an occasional bounce.

The sticky habitats where tautog reside can make hooking and landing them a challenge. Leave the light tackle at home, and pack plenty of extra rigs.

These fish have small mouths, so hooking them can be problematic. You must be patient, wait through their incessant nibbling, be able to feel when the fish actually swallows the bait, and strike quickly and hard when the time is right. They are also black-belt bait stealers, so reel up and check your bait frequently if you’re getting nibbled.

Tautog use their goofy-looking conical teeth to crush the shells of mussels, clams, small lobsters, barnacles, and crabs, which make up the majority of their diet. This menu also adds to their own taste on the dinner table, and their flesh has similarities to crab meat, both in flavor and in texture.

Of all the fishes in the sea, many chefs consider the tautog to be the finest available for making the perfect fish chowder. Many other fish, such as flounder, fluke, or cod, are too soft, and their flesh disintegrates after extensive cooking. Tautog fillets, however, are quite firm and hold together even after being thoroughly cooked.

While clam chowder has managed to become a staple dish at just about every seafood shanty around, fish chowder, for whatever reason, has never really caught on to the same degree. This is a shame! I will gladly take a bowl of good fish chowder over a bowl of clam chowder.

Over the years, I’ve experimented with dozens of different clam and fish chowder recipes, all of which were acceptable. It seems there are many variations between the recipes I’ve found, and no two chefs seem to make a chowder the same way. Following is my own prized recipe that I’ve developed after much experimentation. I use basically the same ingredients for both clam and fish chowder, with the stock being the only difference.

The Zen of Chowder

Any good chowder begins with a good stock. The stock is the backbone of a chowder. If there’s one place to step up your game, this is it. Do not compromise this dish with store-bought fish stock with unknown origins. Make it yourself; you will not regret the extra effort. After you’ve filleted your fish, remove the head and set aside the racks, fins, and any leftover scraps. (Many people include the fish heads in the stock, but I don’t like the gross stuff that seeps out of it after extensive cooking, and the backbones alone add plenty of flavor.) Now it’s time to rock your stock.

Fish Stock

Fish stock can be used in soups, chowder, cioppino, risotto, and so much more. It’s a wonderful way to use up the scraps left over after filleting, and it’s easy to make. It’s also a good way to make use of other food waste. I like to keep a bag of vegetable scraps in my freezer, like carrot tops and onion peels, for making stock. If available, I also include scraps from fennel bulbs and mushroom stems.

Fish bones (and their fins) contain a good amount of collagen, which will thicken the stock a bit. Avoid using the gills or any of the dark red meat on a striper, as these will give your stock an off-putting flavor.

2 to 3 pounds fish parts

2 tablespoons olive oil

Peels from 2 to 3 onions

Base of a head of celery, chopped

1 carrot, chopped

2 bay leaves

10 whole peppercorns (optional)

1 sprig of thyme

1/2 cup dry white wine

Water

Heat the olive oil in a large pot on medium heat. Add the vegetables and cook, stirring often, for about 10 minutes. Add remaining ingredients and enough water so that everything is covered by about one inch. Cover, reduce heat to low, and simmer for 45 minutes. Do not allow it to boil.

Remove from heat and pour through a fine-mesh strainer into a bowl. Give it a taste and add more salt, if needed. I’ve been known to drink this stuff.

Tautog Chowder (for 6-10)

3 cups fish broth

3 cups tautog fillets, skinned, cut into 4-ounce chunks

3 cups red bliss potatoes, cubed

3 cups yellow onion, diced

1 1/2 cups bacon, diced

2 sprigs fresh dill

3 sprigs fresh thyme

1 10-ounce can evaporated milk

2 cups whole milk

1 cup light cream

4 tablespoons butter

4 tablespoons flour

Salt and pepper to taste

Dice up the bacon and add it to your pot. (if you freeze it for 15 minutes, it’s easier to chop.) Cook over medium heat until it’s nice and crispy and all the fat has rendered out. Scoop out the bacon bits and set them aside on a paper towel. (I need to hide them somewhere out of sight, so I don’t nibble them up before the chowder’s finished.)

Drain out any excess bacon fat but leave about a tablespoon in the pot. Add onions and cook them over medium heat until they are translucent, about 10 minutes. I like to constantly season things as I go along, so add in a pinch of thyme and dill, and a crack of black pepper, but resist salting until just before serving. If your onions are starting to stick to the bottom of the pan, add a spoonful of fish broth to help soften them up.

Once the onions are cooked, toss in the ‘taters and stir them around. Add the fish stock, it should just cover the potatoes, cover, and simmer on medium heat for about 12 to 15 minutes, until the potatoes are soft. (I like to mash some of them up to help thicken the chowder.) Add more fish stock if necessary to keep the ‘taters submerged in liquid at all times. Once again, add in a pinch of thyme and dill and season as you go along.

During the cooler fall months, a hearty tautog chowder is an excellent option to warm up friends and family.

Now add the fish. If I’m in a rush, I simply drop the fillets into the pot. If I have the time, however, I’ll dust them in flour and then saute them in butter or olive oil for about 3 minutes per side, until they are just turning golden-brown. This will add a nice extra bit of texture to the final dish, and the flour will help thicken the chowder a bit. After you add the fillets, cover the pot and cook on low for about 10 to 15 minutes. This will allow time for those precious juices to simmer out of those wonderful ‘tog fillets. Once the fish begins to fall apart, it’s time to turn the heat off and add cream and evaporated milk.

Next up is the roux, which will serve to thicken our chowder. In a separate saucepan melt the butter on medium-low heat and then use a spatula to work in the flour. Mix it together until you have a smooth, bubbly paste. Now add the remaining the milk. (If you have no fear of cholesterol, or your weight, use cream, but it’s still decadent enough when made with whole milk.) Bring it to boil on medium heat, stirring constantly, and cook for one minute, then pour it into the chowder pot.

Next, simply do nothing. Cover the pot and let it sit. Grab a beer, watch some football and let the chowder rest for at least a half-hour, the longer, the better. This is where the magic happens. All the flavors will snuggle up together, the ‘taters will suck them in, and our chowder will intensify. Chowder is one of those rare things in life that actually improves with age. I find that my chowder is often tastiest two or three days after I make it.

When you are ready to serve, heat it up on medium heat and stir it frequently. Add more milk if it looks too thick, or add more roux if you want it thicker. Give it a taste and add more salt, pepper, or herbs accordingly.

It’s imperative that our chowder never reaches a boiling point, which is 212 degrees. If the chowder boils it could “break.” When this happens the fat in the milk will coagulate and form small clumps that look unappetizing and ruin the texture. I like to keep a kitchen thermometer on hand and monitor it closely. As soon as it hits 190 degrees, turn off the heat.

Finally, it’s time to serve up some heaping bowls of hot, steaming chowder. Did you forget about those bacon bits? I didn’t! It’s time to remove them from hiding and give each serving a liberal douse of crispy bits. This will serve as a wonderful garnish and the bacon will add some crunch, giving a nice texture and flavor to the final product.